Back in the 1600s, people used auxiliary ‘be‘ + some verbs of motion, where today we’d use ‘have‘.

Shakespeare did it with ‘is fled‘.

LENNOX

‘Tis two or three, my lord, that bring you word

Macduff is fled to England.

And ‘is come‘.

LUCILIUS

He is at hand; and Pindarus is come

To do you salutation from his master.

I thought it would be fun to check it in Google Books Ngram Viewer, and see when ‘has X-en’ became more popular than ‘is X-en’. But you can’t do it with any old verb like ‘make’ — it has to be intransitive. Otherwise, you’re scooping up ‘is made’ constructions like ‘That’s how rubber is made.” Those are still okay now. I want the ones where ‘is X-en’ has been replaced by ‘has X-en’. And the pattern seems particularly common with verbs of motion.

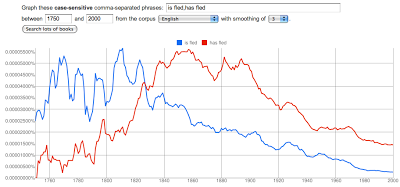

Here’s ‘fled‘. Notice that the crossover happens around 1830ish.

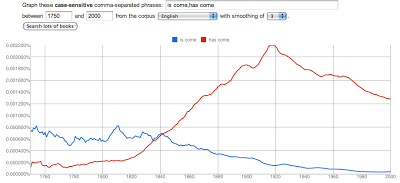

And ‘come‘. They cross over at about the same time: 1840ish.

‘Arrive‘ arrives early — about 1810ish

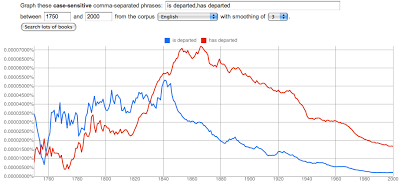

Here’s ‘depart‘, right on the button — 1830 again.

And we see more or less the same pattern with other verbs like land, and become.

What was happening in English in 1800–1840?

When I raised this to the attention of fellow linguist Mark Ellison, he suggested twiddling the ‘Corpus’ menu between ‘British’ and ‘American’. This revealed that the stodgy conservative British books held onto the old usage longer. Perhaps the Americans were at the head of this ‘is – has’ innovation, and the rise we see in the corpus was partially due to more books being published in the Colonies.

I’ll have to do some looking around to see if anyone knows more about it. Luckily, I have two experts on present perfect in my very own department. Meanwhile, I think it’s cool that I can search centuries of language patterns in seconds.

Recent Comments